Brain Research in Early Childhood: A Primer for Caregivers and Administrators (2001)

Feel free to print and/or copy any original materials contained in this packet. KITS has purchased the right to reproduce any copyrighted material included in this packet. Any additional duplication should adhere to appropriate copyright law.

The example organizations, people, places, and events depicted herein are fictitious. No association with any real organization, person, places, or events is intended or should be inferred.

Compiled by Tammie Benham and David P. Lindeman

March 2001

Kansas Inservice Training System

Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities

Adapted for accessibility and transferred to new website October 2022

Kansas Inservice Training System is supported though Part C, IDEA Funds from the Kansas Department of Health and Environment.

The University of Kansas is and Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer and does not discriminate in its programs and activities. Federal and state legislation prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, religion, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, age, disability, and veteran status. In addition, University policies prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, marital status, and parental status.

Letter from the Director

March 2001

Dear Colleague,

The abundance of information concerning research on the development of the brain in young children can be overwhelming. Some of the information is quite technical and rooted in the basic sciences, which can be difficult to understand. Other pieces of this information have the ability to excite our imagination as we begin to understand the learning potential of infants, toddlers and young children. As educators it is our responsibility to take this information and apply it to our educational practice as we interact with young children and families. If used appropriately this information can and will have a significant effect upon our practice.

This packet is an effort to present basic information and provides a starting point for you and your colleagues to understand the intriguing world of the development of the brain. Information is also provided that will give some guidance in the development of educational policy and the “how’s” and “why’s” your community should support early education

Gathering this information has been a collaborative effort of many individuals. KITS is especially grateful for the work of Tammie Benham, the coordinator of the KITS Early Childhood Resource Center. The staff would also like to thank Marnie Campbell and Gayle Stuber for their review of earlier drafts of this packet.

We hope you will find that the packet contains helpful information. After you have examined the packet, please complete the evaluation found at the end of this packet. Thank you for your interest and your efforts toward the development of quality services and programs for young children and their families.

Sincerely,

David P. Lindeman, Ph.D.

KITS Director

Introduction to Brain Research in Early Childhood: A Primer for Caregivers and Administrators

Current brain research shows the more neural connections are used, the stronger they become. This packet was developed with the hope that your interest in this topic will continue beyond the materials that are presented here. A bibliography of suggested resources is included. Having requested this information, it is evident you are interested in keeping abreast of the latest developments in this field. With this in mind, please take the time to review each of the materials presented in this packet, even if you feel you already know the information.

What the Research Tells Us

Parents and experts have long known that babies raised by caring adults in safe and stimulating environments are better learners that those raised in less nurturing settings.

Research has shown:

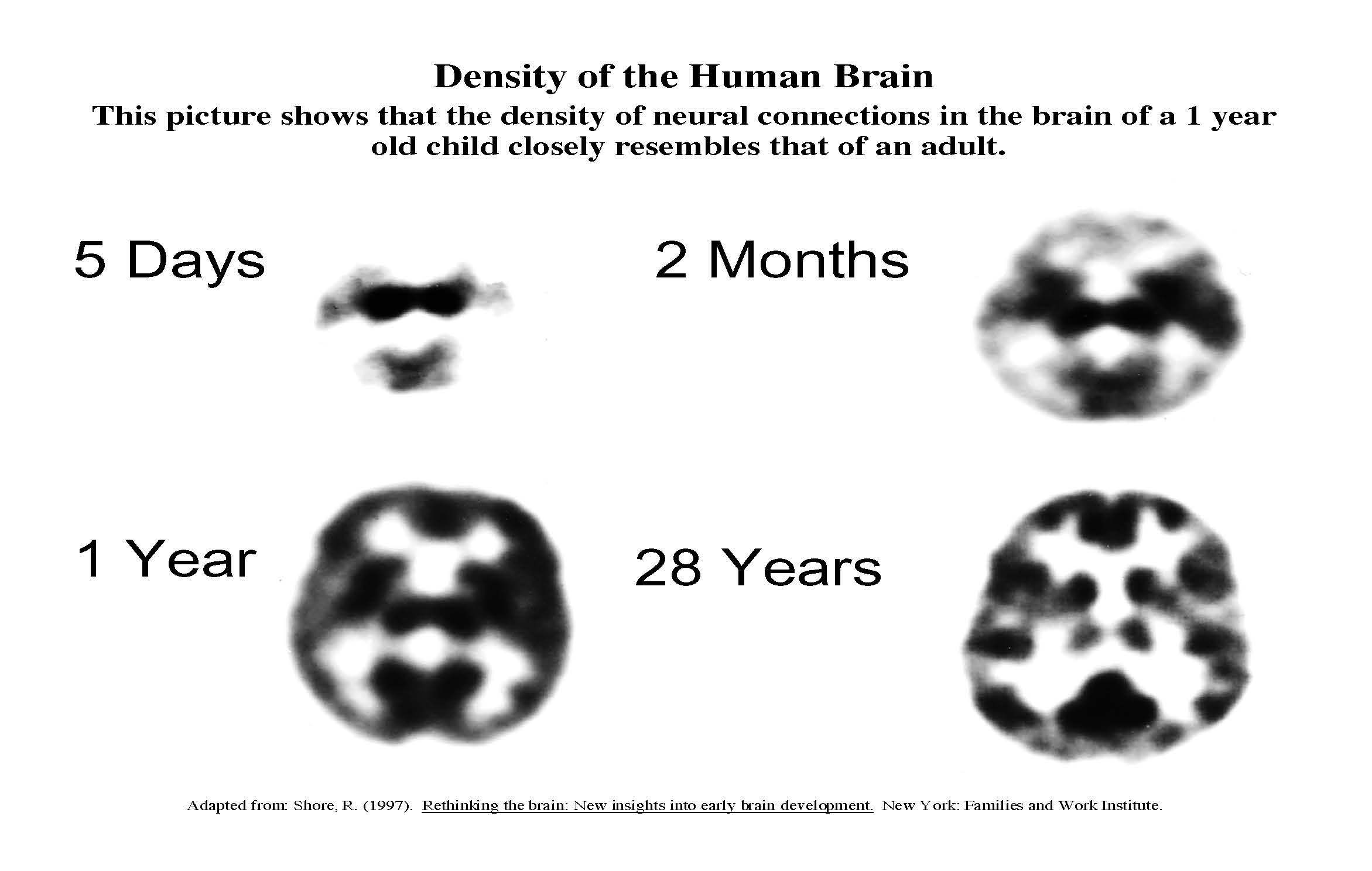

- The brain develops more rapidly before age one than at any other point in a person's life. Biochemical patterns of a one-year-old's brain strongly resemble those of a normal young adult. Connections between neurons multiply at an exceedingly fast rate during the first year of life.

- Upon birth, the brain has already begun to link billions of cells together - up to 15,000 connections (synapses) per cell. These synapses form the brain's physical "maps" that allow learning to take place, and over time, largely determine the intellectual and emotional capacity of the child. The number of synapses increase 20-fold, from 50 trillion to 1,000 trillion, in the months after birth

- Brain development is extremely susceptible to environmental influence. The quality and variety of the physical and emotional environment are very important. Studies of children raised in poor environments show that they have cognitive deficits of substantial magnitude by 18 months of age. Full reversal of these deficits may not be possible.

- The influence of the early environment on the brain development is long lasting. The positive effects of early nurturing appear to accumulate over time. One study followed two groups of inner-city children. The first group was exposed from early infancy to good nutrition, toys and playmates; the second group was not. The first group demonstrated significantly more complex brain function at age 12. There continue to be gains at age 15, suggesting that over time, the benefits of early intervention are cumulative.

- Early stress can impair brain function. A child's social environment can activate hormones, such as seratonin and cortisol, in ways that adversely affect brain functions, including learning and memory. These effects may be permanent. Children who have experienced extreme stress in their earliest years have proven to be at greater risk for developing a variety of cognitive, behavioral and emotional difficulties.

Adapted from:Kids Count in Colorado. (1997). Ensuring the future of our children: Brain child. Denver: Colorado Children's Campaign. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.coloradokids.org/brain.htm - Webpage has since been removed.

Early Childhood Development and Learning: Key Lessons

The impact of early experience on early brain development is powerful and specific, and may last a lifetime. This is a major finding of recent brain research, and it represents a sharp departure from centuries-old ideas about how children develop and grow.

- Early experience affects how brains are “wired”. At birth, children’s brains are in a surprisingly unfinished state. Newborns have all of the billions of brain cells, or neurons, they will need for a lifetime of thinking, communicating, and learning. But these neurons are not yet linked into networks needed for complex functioning. Our initial immaturity gives us a powerful evolutionary edge.Humans have found ways to adapt to almost any habitat on earth. Why? In large part, because so much of our brain development takes place through contact with our environment. This makes humans uniquely flexible and adaptable.

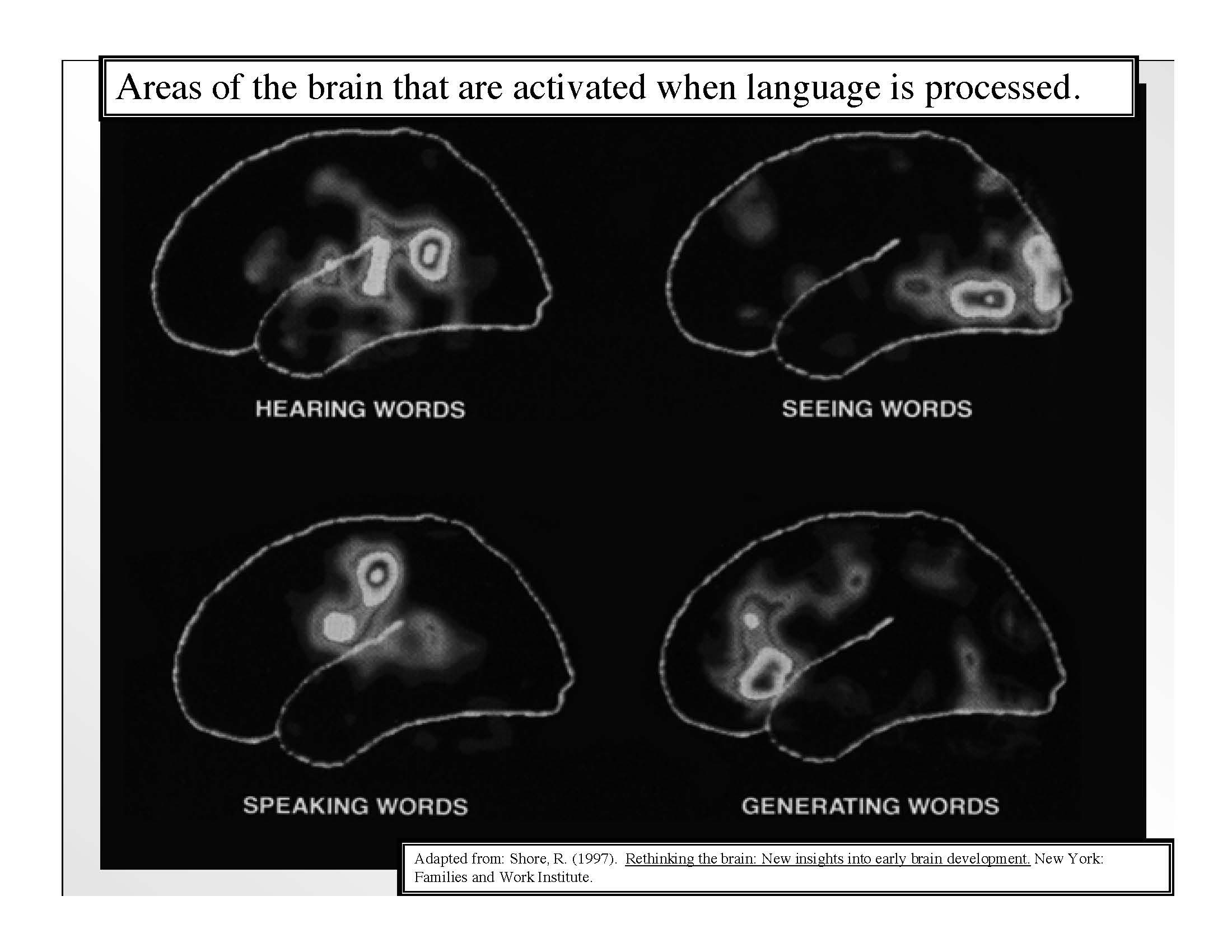

- The young brain is a work in progress. A young child’s brain is a work in progress, and scientists are now able to watch it unfold. Scientists can use new technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography scans (PET scans) and magnetoence phalogram, to see how the brain looks and functions at different stages of development, including in the months before birth.Crucial steps in brain development take place early in pregnancy, before many women know that they are expecting. At birth, newborns cannot yet make sense of the flood of sensation and information that comes their way. However, as new experiences occur, young children’s brains respond by forming and then reinforcing trillions of connections, or synapses, among neurons. Connections form so quickly that by the time children are three, their brains have twice as many synapses than they will need as adults. What happens to the excess connections? They are pruned as children grow, in order to streamline the neuro-network and make it more efficient. Those connections that are used often enough tend to survive; those that are not used often enough vanish.

- Every child is unique. Because experience so powerfully affects early development, no two brains grow and mature in the exact same way. Children are individuals right from the start, even if they are raised in the same culture, locality, or even household. Even the brains of identical twins develop differently, based on their early surroundings and their individual interactions with the adults who care for them. The new brain research answers many questions about how children grow and develop, but it does not diminish the reality that every life is unique and complex.

- Children learn in the context of important relationships. What kind of experiences do infants and toddlers need? Researchers are finding that, more than anything else, young children need secure attachments to the adults who care for them. Babies respond to touch, sounds, images, tastes, and smells. They are at ease when they receive warm, responsive care geared to their needs, moods, and temperament. When this kind of care comes consistently from the same adult or adults, young children form secure attachments. When children form such relationships, their development tends to flourish. What matters to young children is an adult’s ability to understand their needs and to read their signals most of the time, to respond with warmth and affection, to model the pleasures of conversation and turn-taking, to protect them from life’s minor bumps and bruises as often as possible, and to shield them from neglect and abuse.

- Other caregivers can meet young children’s needs, but don’t take the place of Mom or Dad. Research shows that children are capable of forming strong attachments to more than one adult, but not all attachments are equally strong or compelling. Babies tend to prefer their primary caregiver, usually mom. But they quickly learn that other people can meet their needs, and that different people have different ways of caring for them. In this way, they begin to get a sense of life’s complexity and richness. Child care providers can be important people in young children’s lives, but they do not take the place of parents. Recent studies show that high-quality child care does not disrupt young children’s attachments to their parents, as long as parents spend enough time with their infants and toddlers to know them well, care for them confidently, and read their signals and cues.

- “Small talk” has big consequences. Adults have special ways of talking to children that help them master language. Speakers of “parentese” often set their words to enticing melodies that act as acoustic hooks, pulling the baby’s attention to them. But some caregivers do not realize the importance of talking to their children in the first year, even before their children are old enough to begin talking back. Research suggests that their children may be missing out on important learning opportunities. Linguistic experience constitutes a critical part of the setting in which young children grow up, and can have a positive or negative effect on children’s development. Once caregivers know about this kind of research, most will want to make “small talk” with their infants more frequently, warmly, and responsively, and they will want to be sure that child care providers are talking with their babies as well.

- Children need a variety of stimulating activities. Children need opportunities for a variety of vigorous, safe, appropriate physical activities. They need touch, sounds, and images. They need social and emotional contact. And they need thought-provoking activities. Most adults who care for children have some awareness of these needs, but despite parents’ best intentions, many infants and toddlers do not get enough intellectual stimulation. On the other hand, just as too little stimulation can hinder brain development, so can over-stimulation. Children will demonstrate intolerance of over-stimulation in a variety of ways ranging from falling asleep to screaming uncontrollably. Young children have different temperaments and moods. Aside from seeing to their children’s basic health and safety, the most important thing caregivers can do is to learn to read their children’s moods and preferences and whenever possible, adjust activities, schedules, and even the way they touch and talk to their young children.

- Prevention is crucial. The brain does not develop all at once. Different parts of this complicated organ mature at different times and at different rates. Although development continues throughout life, there are periods of great opportunity (and risk) when a particular part of the brain is the site of intensive wiring and is therefore especially flexible. These are known as “windows of opportunity,” or “critical periods”. The concept of critical periods helps to explain why the early years are so important, and why it can be difficult for caregivers and teachers to compensate for experiences that were missed in the first years of life. The bottom line is that in the early years of life, prevention and early intervention are crucial. When health problems are addressed, when family stress is reduced, when mothers seek treatment for depression, young children tend to fare better. The earlier the intervention, the better. The more follow-up, the better. These are simple lessons. As they are applied more widely, results for young children are bound to improve.

- Know your baby. Unconditional love goes to the heart of what it means to be a caregiver. But love is not enough. From a child’s viewpoint, good care is responsive care. It requires getting to know a particular child very well. This is not simply a matter of instinct or affection, it usually takes time and practice and help from more experienced caregivers. No caregiver gets it right every time. In fact, the ups and downs are among the experiences that help the brain to mature. What’s more, when children have a secure attachment to the adults who care for them, they are forgiving. When a caregiver disappoints them, they usually offer another chance. However, some mistakes cannot be tolerated. There is never an excuse for abuse or neglect, or for household dangers that imperil children’s lives.

Adapted from: U.S. Department of Education. (1999, September). How are the children? Report on early childhood development and learning. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from the World Wide Web: http://www.ed.gov/pubs/How_Children/IIEarlychildhood.html#1 - Webpage has since been removed.

What is Essential for Optimum Brain Development

All children need and benefit from:

- Emotionally responsive, dependable, educated, healthy, economically stable, and trusting parents;

- Intensive nurturing;

- A rich and responsive language environment in which children are exposed to a wide vocabulary and are read to every day;

- Full-day, five-day-a-week, year-round care and education (whether provided by parents or other significant caregivers) that keep children safe and provide consistent, enriched learning environments with toys, playmates; and developmentally appropriate challenges.

Children need and benefit from the additional support of:

- Prenatal care that emphasizes nutrition and healthy behavior;

- Parent education in child-rearing skills and development;

- Home visits by health professionals for premature babies;

- Preventative health care with follow up services that alerts parents to hearing, vision, and learning difficulties before easily treated ailments, such as ear infections, result in permanent damage; and

- Home visits by child development professionals supplemented with comprehensive, early, center-based care and education.

Results of Appropriate Early Years

With a nurturing environment early in life, all children:

- Adjust more easily to school, have better cognitive and language development, are less likely to repeat a grade, and are assigned to special education programs less frequently, and

- Are more likely to be emotionally competent, well adjusted, responsible, and able to control violent impulses.

All children can benefit from brain development research. Targeted programs have been shown to:

- Double the growth rate and increase IQ scores of premature babies;

- Improve IQ scores an average of 20 points for children of impoverished parents;

- Achieve normal functioning in children with mild retardation;

- Improve rates of graduation, secondary education or training, employment; and annual earnings among disadvantaged children.

Adapted from: Kids Count in Colorado. (1997). Ensuring the future of our children: Brain child. Denver: Colorado Children’s Campaign. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.coloradokids.org/brain.htm - Webpage has since been removed.

Helping the Brain Grow

10 Things That Can Boost Your Child’s Brain Power (And your child will love every one of them!

- Interaction: Your consistent, long-term attention actually increases your child’s capacity to learn.

- Loving Touch: Holding and cuddling does more than just comforting your baby—they aid brain growth.

- Stable Relationships: Relationships with parents and other caregivers decrease harmful stress.

- Safe, Healthy Environments: Should be free of lead, loud noises, sharp objects and other hazards which could diminish healthy brain growth.

- Self-Esteem: Grows with respect, encouragement and positive role models from the beginning.

- Quality Child Care: Trained teachers and family child care providers can make a positive difference.

- Play: Helps your child explore the senses and discover how the world works.

- Communication: Talking with your baby builds verbal skills needed to succeed in school and later in life.

- Music: Expands your child's world, teachers new skills and offers a fun way to be with you.

- Reading: Reading to your child from the beginning shows its importance and creates a lifelong love of books.

Adapted from: McCormick Tribune Foundation. (2000). These 10 things can boost your child’s brain power. Chicago: Author. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from the World Wide Web: http://www.rrmtf.org/education/10things.htm - Website has since been discontinued.

High Quality Early Childhood/Family-Focused Programs That Help Promote Healthy Brain Development Look Like This...

- Accessible and affordable programs housed in appropriate facilities.

- Well-qualified staff, trained in early childhood development with ongoing opportunities and requirements for continuous, professional development.

- Developmentally appropriate curriculum and practices that promote school readiness by enhancing a child’s language, social/emotional, self-help, physical and intellectual skills.

- Small classes with low ratios of children to teachers.

- Adequate financial and physical resources, including staff salaries and benefits.

- Quality standards for health services, nutrition, social services, family involvement, staff qualifications, etc.

- Coordinated services with other agencies or providers to meet children’s multiple needs.

- Ongoing evaluations to ensure program effectiveness.

- Services or resources to foster family involvement.

- Prevention and intervention of at-risk factors associated with poverty.

- Opportunities for families to gain economic self-sufficiency while nurturing their children’s development.

- Support continues as children enter elementary school

Adapted from Education Commission of the States. (1998, March), Policy brief: Why policymakers should be concerned about brain research. Denver: Author.

High Quality Early Childhood Programs

- Blend funding resources to help families meet the costs of child care (e.g., government funding mixed with parent fees).

- Teach child care providers how to create more responsive and intellectually stimulating environments.

- Expand government funds to support full-day, year-round child care programs.

- Support and encourage accreditation of child care programs.

- Offer financial incentives for child care providers to receive higher levels of education.

- Provide fiscal incentives to encourage districts and schools to offer high-quality early childhood and preschool programs.

- Invest in high-quality early childhood programs.

Training and Intervention/Prevention

- Provide preventive and primary health-care coverage for expectant parents and their children.

- Require proper immunizations, and conduct vision, hearing and developmental screenings.

- Offer nutrition programs, home-visitor programs, and caregiver training to improve child care quality.

- Create intervention programs aimed at decreasing and preventing teenage pregnancies, children in poverty, runaways and dropout rates.

- Provide economic supports (e.g., tax breaks, subsidies) which either help to increase the proportion of people who are able to access quality and affordable child care or help family members remain at home with young children.

Adapted from Education Commission of the States. (1998, March), Policy brief: Why policymakers should be concerned about brain research. Denver: Author.

What Parents and Caregivers can do to Stimulate Learning in the Early Years

- Show children you care about them by spending time with them

- Establish a stable relationship with your children.

- Establish daily family routines.

- Read, talk and sing often to your children.

- Build self-esteem in your children.

- Show excitement when your children triumph.

- Hold and comfort your children.

- Interact through play with your children.

- Communicate and model positive values and character traits such as respect, responsibility and honesty.

- Make sure your children have regular checkups and timely immunizations.

- Safety proof your home, and encourage safe exploration and play.

- Listen and respond to your children’s verbal and nonverbal cues and clues.

- Regularly access community resources such as the local library.

- Promote activities that develop your child’s large and small muscles.

Adapted from: Education Commission of the States. (1998, March), Policy brief: Why policymakers should be concerned about brain research. Denver: Author.

Windows of Learning

| Windows of Learning | Birth | 1 Year | 2 Years | 3 Years | 4 Years | 5 Years | 6 Years | 7 Years | 8 Years | 9 Years | 10 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Acuity (How small an object a child can see) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | / | / | ||

| Binocular Vision (How well the eyes work together) | X | X | / | ||||||||

| Stress Response (How a child responds to stress) | X | X | X | X | / | / | / | / | |||

| Empathy/Envy | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | / | / | ||

| Recognition of Speech | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | / | / | ||

| Vocabulary | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Basic Motor Skills (How a child moves in his environment) | X | X | X | X | X | / | / | / | |||

| Fine Motor Ability (How well a child can manipulate small objects) | X | X | X | X | X | X | / | / | |||

| Musical Fingering (ability to connect written music with finger positions on an instrument) | X | X | X |

Key:

X = High Acquisition

/ = Continued Acquisition

Although no one can say when the exact times for learning these concepts start and end, this graph shows the optimal times for children to acquire the skills listed on the left. During High Acquisition the time is most optimal. Learning the skill is still possible, yet more difficult, during the Continued Acquisition phase.

Adapted from Nash, J.M. (1997, February). Fertile minds. TIME Special Report 149(5), 48-56.

Brain Growing Activities

Where does it happen in the brain?

You have probably read an article or seen a TV show that illustrates how experiences your baby has now affect how her brain grows. But do you know that your child’s brain has special areas for different abilities? Do this activity to discover important sections of the brain.

First, put your hands behind your head. This area is the vision center of your brain.

Move your hands down to where your neck just begins, where you feel two bony bulges. This is the cerebellum that is responsible for motor coordination and balance.

Bring your hands to the center of the back of your head and you have found the brain stem that is responsible for automatic bodily functions like your heart beating, breathing and digesting your food.

Now put your hands on your head as if you were putting on a headband. This is the motor sensory area, which allows you to do things like feel the pressure of your foot on the floor as you walk, or the position of your tongue in your mouth as you say particular sounds.

The center for hearing is conveniently located just above your ears.

To find taste and smell, touch the bridge of your nose. The brain center for taste and smell is protected within the brain. Also deep within the brain is the limbic system that is responsible for emotions.

And finally, touch your forehead. That is the frontal lobe that is responsible for higher thinking skills such as solving problems.

Adapted from: Eisenberg, L. (1999). Experience, brain, and behavior: The importance of a Head Start. Pediatrics, 103 (5), 1031.

Brain Growing Activities

- Stimulate vision with mobiles and posters.

- Stimulate hearing with soothing music.

- Entertain babies with a variety of new sensory experiences.

- Provide child-proofed areas for exploration (drawers, sandbox).

- Provide lots of gentle physical affection.

- Comfort a baby whenever he or she is hurt, frightened or insecure.

- Provide appropriate discipline.

- Provide a language-rich environment by:

- Reading to your child;

- Labeling the environment;

- Talking to your child;

- Making up stories with your child; and

- Singing lullabies, kiddie songs, and opera!

- Help children to see and listen in a more discriminating manner. Talking to them about what they see in the pictures of the books you are reading them or the different instruments they hear playing in a classical piece of music will help them develop this skill.

- Provide a calm environment and a regular schedule.

Adapted from: Diamond, M.C., & Hopson, J.L. (1998). Magic trees of the mind: How to nurture your child’s intelligence, creativity, and healthy emotions from birth through adolescence. New York: Plume.

Guidelines for Brain-Building Play

- Make sure the child is actively interested and involved.

- If the child seems passive, start a simple activity and then try to “pass it over.”

- Remember that an activity must be repeated many times to firm up neural networks for proficiency.

- Give the child positive encouragement for active exploration and investigation which builds motor and sensory pathways.

- Encourage attempts at new challenges (in a child-proofed environment).

- Keep playpen time or other restraints to a minimum.

- Provide windows for children to look out.

- Provide low open shelves where a variety of toys, objects, and books are always accessible. Avoid boxes with jumbled toys.

- Bring in new toys or objects one or two at a time.

- Provide an attractive environment with bright colors which can be varied to attract visual attention.

- Call attention to specific objects or aspects of the environment, (help infant to focus on one sense at a time).

- Link language to sensory input. Talk about what is happening.

Adapted from: Healy, J. (1994). Your child’s growing mind: A guide to learning and brain development from birth to adolescence. New York: Doubleday.

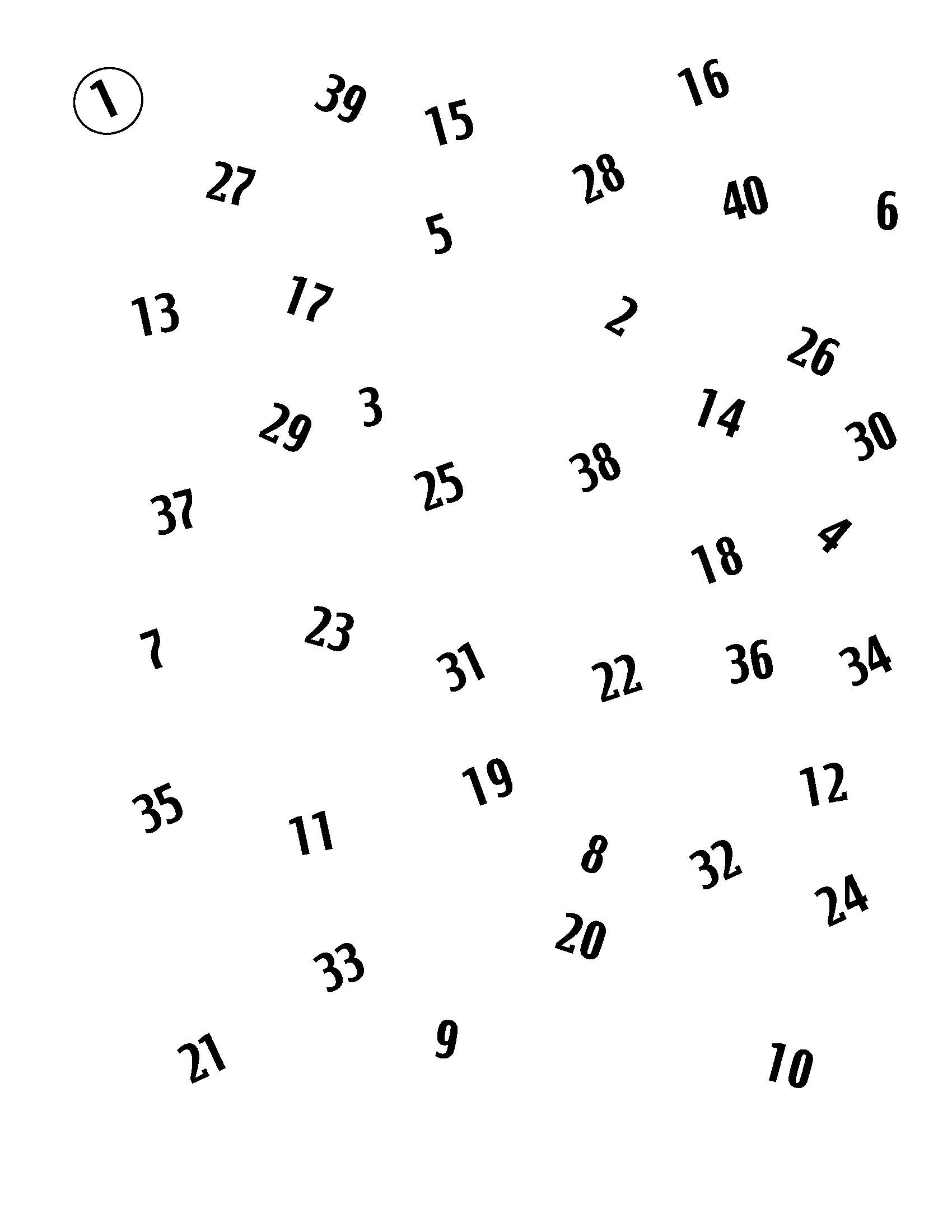

Connect the Neurons

Take this simple test. The following two pages contain a series of numbers randomly placed on a piece of paper. Both pages are the same. Give yourself 30 seconds to connect as many numbers as possible.

After completing the first page, reset the timer and take the test again. Did the number of connections you made go up?

Repetition is important to learning, no matter what the age of the individual. By repeating the process involved in learning or the concept being learned, the neurons (nerve endings in our brain) form stronger, more solid connections. That is why it is not as necessary to concentrate when driving home from work as it is when trying to find an address.

Young children need the same type of repetitive experiences to be successful learners. For example, speaking aloud the name of colors in a toddler’s environment each day will help the child make the connections necessary to put together the visual cue of “red” with the spoken word. Such learning happens when repeated experiences occur in multiple settings and different modalities are used.

Benham, T., & Lindeman, D. P. (2001). Brain research in early childhood: A primer for caregivers and administrators. Parsons, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

Hussey-Gardner, B. (2000, June). Developmental interventions with families and their children: Helping parents make a difference in the brain development of their infants, toddlers and preschoolers. Presentation at the Kansas Inservice Training System Summer Institute, Wichita, Kansas.

Creating Policy Change

Ideas for Policymakers to Help Develop Healthy Brain Development

- Help develop programs that support and strengthen families.

- Value parents’ role in reinforcing the child’s self-worth.

- Help parents develop leadership and child-advocacy skills.

- Reinforce successful child-raising skills with current child development and brain development information and monitor children’s health needs; and provide referrals for service.

- Support coordination and continuity in services.

- Locate or establish an information and resource center for supporting children and families.

- Produce an information/assistance packet for all new parents describing available resources (e.g., parent education programs and community services).

- Inform families about community services (e.g., free days at the museum and story time at the library).

- Encourage and support flexible, family-friendly work arrangements (e.g., job sharing, professional part-time employment, alternative work schedules and flexible leave policies which accommodate school visits and volunteer activities).

- Advocate to improve personnel policies such as supporting child care, maternity and paternity leave, and extended leave policies.

- Offer incentives to businesses for operating early childhood programs for working families.

Adapted from: Education Commission of the States. (1998, March). Policy brief: Why policymakers should be concerned about brain research. Denver: Author

Building on Success

Every sector of our society must be involved in the lives of children to continue improving the quality of early childhood. Here are some suggestions for each sector of society:

Parents and Families

- Show you love your children by:

- Spending time with them

- Chatting with them

- Protecting their health and safety

- Creating predictable routines and consistent time limits

- Stimulate intellectual growth by:

- Reading to them

- Engaging them in age-appropriate activities to tap curiosity and spark creativity

- Become better informed about:

- Parenthood, beginning even before children are conceived

- Family support organizations, childcare centers, libraries, hospital and health clinics, human service agencies, and schools and universities

- Learn about your child by:

- Observing him closely to notice rhythms and preferences

- Respond to signals she sends through body language such as crying, facial expressions and responses to stimuli

- Think about and talk about your own past experiences to gain insight about such things as temper management and responses to crying

Local Communities

- Be involved by:

- Promoting efficient, frequent communication among a wide range of service providers

- Sharing information with other professionals in ways that benefit children and families without violating their rights to privacy

- Monitoring and documenting children’s safety, health and progress toward developmental milestones

- Analyzing factors that promote or hinder healthy development and learning, making changes as needed

- Envisioning a future where children and families will thrive and take steps to move the entire community toward that future

- Helping shape broad-based action strategies aimed at improving life for young children and their families. Some of the universal goals of these strategies are:

- Ensure that every expectant mother receives timely care.

- Give every child access to the health care and support needed to get a good start in life, physically and emotionally.

- Help children build stable, trusting relationships with the adults who care for them.

- Support the adults who influence development and learning, and include both mothers and fathers in all parent involvement efforts.

- Focus on prevention, and respond quickly when problems arise.

- Set high expectations for every child.

- Offer varied, engaging, appropriate activities that foster development, including opportunities for conversation and turn taking beginning in the early weeks of life.

- Make efficient, equitable use of resources, expanding successful efforts and eliminating those that are not effective.

- Collaborate with other institutions.

- Take responsibility for results.

Educational Leaders

- Rethink “Kindergarten Readiness” by:

- Shifting focus from “ready children” to “ready schools”

- Working more closely with the preschools and childcare programs whose children will soon be moving into kindergarten classrooms

- Sharing curricula and professional development opportunities with preschool and childcare staff

- Communicating with and providing support to parents from the time a future student is born

Business Leaders

- Promote family-friendly employee practices by:

- Supporting innovation and research

- Creating or subsidizing childcare programs for employees’ children

- Forming coalitions within the business community to address these issues

- Using products to promote best practices

The Media

- Use the powerful impact of the media in our society to:

- Give parents control over what their children watch with Parental Control options on devices such as iPads and smart TVs (note that, aside from APA formatting, this is the only item that has been updated from the original TA Packet as it had previously suggested use of a media technology that is currently obsolete)

- Support more programming aimed at parents with small children

- Increase educational fare on TV and the radio

- Disseminate new research findings

- Promote more space to children’s issues and communicate the importance of healthy development in the early years of life in print media

- Place appropriate technology in libraries, workplaces, schools, community organizations, museums, housing projects and other places where parents can access the wide array of knowledge available on the internet

- Help families evaluate the knowledge they find on the internet

Government

- Make sure parents have a range of choices about how to raise and care for their young children by:

- Providing the tools and information that can help them make sound decisions Supporting legislation that promotes health, well-being, and learning of young children and their families

- Supporting research

- Disseminating research findings

- Providing technical support to states and communities as they plan, implement, and evaluate new initiatives

- Creating and supporting programs that meet a clear national interest, such as Head Start and Early Head Start

- Keeping children at the top of the agenda

Research

- Continue to strive to reach a deeper understanding of how children grow as well as how families, communities and the nation as a whole can contribute to the next generation’s healthy development by:

- Continuing to value the experiences of families and others who spend days working with families

- Taking into account at every stage of the work the implications of their findings for policy and practice

- Building bridges between research and practice

Adapted from U.S. Department of Education. (1999, September). How are the children? Report on early childhood development and learning. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.ed.gov/pubs/How_Children/IVbuilding.html - Webpage has since been removed.

Advocacy in Early Childhood Services

Utilization of Brain Development Information in Advocacy for Early Childhood Services

The wealth of information related to brain development in young children has provided validation and hard scientific evidence to what many early childhood educators have believed for quite some time — that the early years are truly important in shaping and fostering the development of children. With this information we now have the opportunity to advocate for early childhood services with new pieces of information and in innovative ways. However, advocacy and training of others to support quality services in our communities and schools can seem to be a daunting task – especially when we are working with people we don’t know or those who are in policy making positions. With a little planning the feelings of apprehension can be lessened.

The following are some questions that you might answer in relationship to your reason for using this research on brain development:

- Who is the Target Group?

- Are you using this information to educate a specific target group? Who are the people that you are talking to, what is their relationship to young children, and why do you want to impact their thinking? For different groups you might organize the information differently for the greatest impact. Examples of target groups are many and advocacy/training efforts for each group will probably have a different purpose or outcome. For public figures such as legislators, county commissioners, or school board members, your outcome may be that you want these policy makers to invest financial support in program development or expansion. Therefore, it would be important to discuss not only aspects of positive developmental outcomes but also the potential dollar savings related to less dependence on remedial and special education services. For parents you may want them to understand some of the simple activities they could do to support their child’s development. And a final example, for nurses you may want them to understand the importance of nutrition or specific vitamins on the development of the brain. Other examples of potential target groups include service providers from a variety of fields such as social work, foster care, teaching, or health care; the general public; or administrators of services and programs. You will want to consider for each of these groups how the information will be packaged in a slightly different way or with different content to achieve your goal.

- How do you Want to Use this Information?

- Are you using this information for advocacy? Is your purpose to establish or develop early childhood services for your community or to improve the quality of existing services? If your intent is to use this information for the expansion of current services your message may be somewhat different than information to establish services. A change in content when trying to expand existing services to new groups of children or provide enhanced services could be the potential benefits to all children in the community as opposed to a small group of children. Your intent may only be to inform people with no other specific outcomes identified. This type of sharing may be extremely important as time passes and opportunities change. It may be the seed that grows into an identified plan later.

- How can/or Are You Going to Deliver the Information?

- What will be the method of delivery of information and how might that affect your desired outcome? The delivery of information can take many forms, from traditional workshops, conferences or presentations, to videotape, print materials, web-based delivery, or distance learning environments such as interactive television (ITV). The amount, complexity and depth of information to be provided will determine the method of presentation. For a ten-minute presentation to a school board you would not develop a sophisticated web based presentation. However, you may choose such a method for an in-depth training program to support teachers in their understanding of brain development and how it could affect their teaching method and style.

- Who Are Your Partners?

- Who are or might be your partners in the delivery of training or advocacy for programs and service? This might include parents, state agency personnel, representatives from professional organizations such as the Kansas Division for Early Childhood or the Kansas Association for the Education of Young Children, personnel from programs designed specifically for training such as the Kansas Inservice Training System, the Kansas Association for Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies or the Kansas Child Care Training Opportunities, college/university faculty, educational personnel from the local early intervention network, child care programs, or Early/ Head Start programs, or regional training programs such as the Quality Improvement Center for Early/Head Start, the Quality Improvement Center for Disabilities associated with Early/Head Start, or the Regional Resource Centers. It may be important in order to achieve your desired outcome and reach the targeted group that a collaborative partner facilitates your effort. One advantage may be that this partner already has credibility with the target group that will foster their listening and learning new information.

- What Information Do You Want to Provide?

- As noted above, the amount and type of information that you provide will be dictated by many factors such as audience, amount of time, place, and your goal or desired outcome. This information can range from the physical development of the brain at different time periods in a child’s life to the benefits of early education and intervention and the cost/benefits of early childhood education. You might conduct a community survey or map of existing services and then identify programs or services to fill gaps or improve quality. Therefore, the type and amount of information you provide to a group will reflect your desired outcome.

Benham, T., & Lindeman, D. P. (2001). Brain research in early childhood: A primer for caregivers and administrators. Parsons, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

References

The references in this section were originally written in the APA format standard of 2001. References have been partially updated to reflect modern APA standard (currently APA 7), however, items such as book DOI and website names were not originally recorded.

Articles

Azar, B. (1998). The bond between mother and child. APA Monitor.

Begley, S. (1997). How to build a baby’s brain. Newsweek, Spring/Summer Special Issue, 28-32.

Brain development in infancy. (1997). Unpublished manuscript.

Education Commission of the States. (1996, November). Policy brief: Neuroscience research has impact for education policy. Denver: Author.

Education Commission of the States. (1998, March). Policy brief: Why policymakers should be concerned about brain research. Denver: Author.

Eisenberg, L. (1999). Experience, brain, and behavior: The importance of a Head Start. Pediatrics, 103 (5), 1031.

Kansas Action For Children, Inc. (1997). Brain growth versus Kansas public expenditures on children ages 0-18. Topeka: Author.

Lindsey, G. (1999). Brain research and implications for early childhood education. Childhood education, 75(2).

Puckett, M., Marshall, C.S., & Davis, R. (1999). Examining the emergence of brain development research: The promises and the perils. Childhood Education, 76(1), 8-12.

Smith, R.M. (2000) Your child. Newsweek, Special Edition, CXXXVI(17A).

Sylwester, R. (1995). A celebration of neurons: An educator’s guide to the human brain. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Books

Beck, J. (1983). Best beginnings: Giving your child a head start in life. New York: Putnam.

*Bruer, J.T. (1999). The myth of the first three years: A new understanding of early brain development and lifelong learning. New York: Simon and Schuster. (ECRC catalog number PM-2.817)

*Caine, R.N., & Caine, G. (1994). Making connections: Teaching and the human brain. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley. (ECRC catalog number PM-2.808)

Diamond, M.C., & Hopson, J.L. (1998). Magic trees of the mind: How to nurture your child’s intelligence, creativity, and healthy emotions from birth through adolescence. New York: Plume.

*Fox, N., Leavitt, L., & Warhol, G. (1999). The role of early experience in infant development. Washington, DC: Teaching Strategies. (ECRC catalog number CM-5506)

Gopnick, A. (1999). The scientist in the crib: Minds, brains, and how children learn. New York: William Morrow.

*Hannaford, C. (1995). Smart moves: Why learning is not all in your head. Arlington, VA: Great Ocean Publishers. (ECRC catalog number CM-6017)

Healy, J. M. (1994). Your child’s growing mind: A guide to learning and brain development from birth to adolescence. New York: Doubleday.

Hussey-Gardner, B. (1992). Parenting to make a difference (one to four years). Palo Alto, CA: Vort.

Kotulak, R. (1996). Inside the brain: Revolutionary discoveries of how the mind works. Kansas City, MO: Andrews & McMeel.

*Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. (ECRC catalog number PM-227)

*Shore, R. (1997). Rethinking the brain: New insights into early brain development. New York: Families and Work Institute. (ECRC catalog number CM-4028)

*Trister-Dodge, D. & Heroman, C. (1999). Building your baby’s brain: A parent’s guide to the first five years. Washington, DC: Teaching Strategies. (ECRC catalog number PM-678)

Videos

*Discovery Channel. (1996). The brain, our universe within, evolution and perception. Bethesda, MD: Discovery Communications. (ECRC catalog number PMV-305.2)

*Discovery Channel. (1996). The brain: Our universe within, matter over mind. Bethesda, MD: Discovery Communications. (ECRC catalog number PMV-305)

*Discovery Channel. (1996). The brain: Our universe within, memory and renewal. Bethesda, MD: Discovery Communications. (ECRC catalog number PMV-305.3)

*McCormick-Tribune Foundation. (1997). Ten things every child needs. Chicago: Author. (ECRC catalog number CMV-4005)

*National Association for the Education of Young Children. (1999). Cooing, crying and cuddling, infant brain development. Washington, DC: Author. (ECRC catalog number PMV-200)

*Reiner, R. (1997). I am your child: The first years last forever. Los Angeles: Warner Media. (ECRC catalog number CMV-4006)

*Start now! empieza ya ! (1999). Chicago: El Valor. (ECRC catalog number CMV-4003)

*These items are available from:

KITS Early Childhood Resource Center

2601 Gabriel, Parsons, KS 67357

Email: resourcecenter@ku.edu

Phone: 620-421-3067

Website References

Please note that as these websites were referenced in 1997 - 2000, all of them have either since been removed or have moved to new locations.

Bales, D. (1998). Building baby’s brain: Ten myths. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, College of Family and Consumer Sciences. Retrieved September 9, 1999, from http://www.fcs.uga.edu/pubs/current/FACS01-2.html

Bales, D. (1998). Building baby’s brain: The basics. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, College of Family and Consumer Sciences. Retrieved December 9, 1999, http://www.fcs.uga.edu/pubs/current/FACS01-1.html

Bower, D. (1998). Building baby’s brain: Prime times for learning. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, College of Family and Consumer Sciences. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.fcs.uga.edu/pubs/current/FACS01-3.html

Dana Foundation. (2000). The brain web and brain information. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.dana.org/brainweb/

Library of Congress. (2000). Project on the decade of the brain. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://lcweb.loc.gov/loc/brain/

Markezich, A. (2000). Learning windows and the child’s brain. Superkids Educational Software Review. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.superkids.com/aweb/pages/features/early1/early1.shtml

Nash, J.M. (1997, February). Fertile minds. TIME Special Report 149(5). Retrieved December 9, 1999, from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,985854,00.html

Neuroscience for Kids. (2000). Brain development. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/dev.html

Online NewsHour. (1997, May 29). Child’s play. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/youth/jan-june97/brain_5-29.html

Science Daily. (1999). Baby talk: Parents do make a difference by promoting childhood chatter, from birth to age 3. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1999/04/990420064552.htm

U.S. Department of Education. (1999, September). How are the children? Report on early childhood development and learning. Retrieved March 21, 2000, from http://www.ed.gov/pubs/How_Children/IIEarlychildhood.html-1

Packet Evaluation

Please take a few minutes to complete the brief online survey above. Your feedback is central to our evaluation of the services and materials provided by KITS.